Meanwhile in Providence a young boy growing with the passion of astronomy: Howard Phillips Lovecraft, in a letter to Rheinhart Kleiner on 16 November 1916, wrote:

In the summer of 1903 my mother presented me with a 2-1/2" astronomical telescope, and thenceforward my gaze was ever upward at night. The late Prof. Upton of Brown, a friend of the family, gave me the freedom of the college observatory, (Ladd Observatory) & I came & went there at will on my bicycle. Ladd Observatory tops a considerable eminence about a mile from the house. I used to walk up Doyle Avenue hill with my wheel, but when returning would have a glorious coast down it. So constant were my observations, that my neck became much affected by the strain of peering at a difficult angle. It gave me much pain, & resulted in a permanent curvature perceptible today to a close observer.(1)Thanks to this passion for cosmos, Lovecraft starting to write The Rhode Island Journal of Astronomy:

In January, 1903, astronomy began to engross me completely. I procured a small telescope, and surveyed the heavens constantly. Not one clear night passed without long observation on my part, and the practical, first-hand knowledge thus acquired has ever since been of the highest utility to me in my astronomical writing. In August 1903 (though I knew nothing of the press associations) I commenced to publish an amateur paper called The R.I. Journal of Astronomy, writing it by hand, and duplicating it on a hectograph. This I continued for four years, first as a weekly, later as a monthly.(1)he wrote in a letter to Maurice W. Moe, on 1 January 1915.

In this way he could perform a lot of observations and he also supposed the possible existence of a new planet beyond Neptune, like he wrote on a letter to the Scientific American:

In these days of large telescopes and modern astronomical methods, it seems strange that no vigorous efforts are being made to discover planets beyond the orbit of Neptune, which is now considered the outermost limit of the solar system. It has been noticed that seven comets have their aphelia at a point that would correspond to the orbit of a planet revolving around the sun at a distance of about 100 astronomical units (9,300,000,000 miles).In our story there is another great people that searched the new planet: the astronomer Percival Lowell, that Lovecraft known in 1907. Indeed, in another letter to Rheinhart Kleiner dated 19 February 1916, he remembered:

Now several have suggested that such a planet exists, and has captured the comets by attraction. This is probable, as Jupiter and others also mark the aphelia of many celestial wanderers. The writer has noticed that a great many comets cluster around a point 50 units out, where a large body might revolve. If the great mathematicians of the day should try compute orbits from these aphelia, it is doubtful if they could succeed; but if all the observatories that possess celestial cameras should band together and minutely photograph the ecliptic, as is done in asteroid hunting, the bodies might be revealed on their plates. Even if no discoveries were made, the accurate star photographs would almost be worth the time and trouble.(2)

As to celebrities—one experience of mine had to do with an astronomical instead of a poetical giant; namely, Percival Lowell, the brother of Pres. Lowell of Harvard, and the widely known observer of Mars—whose observatory is in Flagstaff, Arizona. He lectured in this city in 1907, when I was writing for the Tribune, and Prof. Upton of Brown introduced me to him before the lecture in Sayles' Hall. Now here is the amusing part—I never had, have not, and never will have the slightest belief in Lowell's speculations; and when I met him I had just been attacking his theories in my astronomical articles with my characteristically merciless language. With the egotism of my 17 years, I feared that Lowell had read what I had written! I tried to be as noncommittal as possible in speaking, and fortunately discovered that the eminent observer was more disposed to ask me about my telescope, studies, etc., than to discuss Mars. Prof. Upton soon led him away to the platform, and I congratulated myself that a disaster had been averted!(1)Lowell started his searching program in 1906

(...) using a camera 5 inches in aperture to record photographically the positions of the many thousand of faint stars, for purposes of comparison.(3)Unfortunately he could not find the new planet, but he resumed the program in 1914. He completed his work in 1916, but examining data he didn't find the planet X: he simply could predict some properties of this elusive object:

(...) "Planet X" had a mass 1/50000 that of the Sun, or 7 times that of the Earth, and a mean distance of 43 astronomical units from the Sun.(3)Another attempt was performed by W. H. Pickering in 1919, but without any result. Despite this new failure, Lawrence Lowell, Percival's brother, funded the Lowell Observatory in order to find the new planet. And in January 1929 V. M. Slipher, the director of the Observatory, invited Clyde Tombaugh to join the challenge. Slipher's choice was succesfull: on the afternoon of February 18, 1930, Tombaugh observed the first image of Pluto:

The experience was an intense thrill, because the nature of the object was apparent at first sight.At the same time Lovecraft was writing The Whisperer in Darkness where he described the planet Yuggoth, that he became another version of Pluto after the official announcement of the discover on March 13, 1930.

(...)

The images were sharp, not diffuse; hence, there was no suggestion that the object was a comet. In all of the 2 million stars examined thus far, nothing had been found that was as promising as this object. It was about two magnitudes brighter than the faintest stars recorded on the plates. At once the 5-inch plates, taken simultaneously, were inspected with a hand magnifier. There too were the images of Pluto, clearly confirmed, exactly in the same positions!(3)

In a letter to Miss Elizabeth Toldridge, 1 April 1930, he wrote:

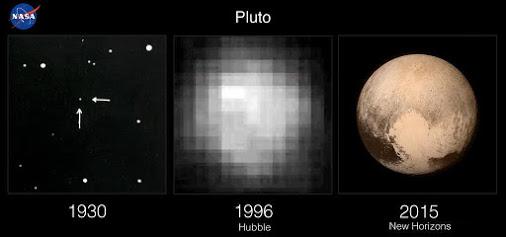

Incidentally—you have no doubt read reports of the discovery of the new trans-Neptunian planet . . . . a thing which excites me more than any other happening of recent times. Its existence is no surprise, for observers have long known that one or more such worlds probably exist beyond Neptune; yet its actual finding carries hardly less glamour on that account. Keats (thinking no doubt of Herschel’s discover of Uranus in 1781, or perhaps of the finding of the earlier asteroids) caught the magic of planetary discovery in two lines of his Chapman’s Homer sonnet, & that magic is surely as keen today as then. Asteroidal discovery does not mean much—but a major planet—a vast unknown world—is quite another matter. I have always wished I could live to see such a thing come to light—& here it is! The first real planet to be discovered since 1846, & only the third in the history of the human race! One wonders what it is like, & what dim-litten fungi may sprout coldly on its frozen surface! I think I shall suggest its being named Yuggoth! Reports make it smaller than Uranus & Neptune, but larger than the earth. I shall await its ephemerides & elements with interest. Probably it will receive a symbol & be treated of in the Nautical Almanack—I wonder whether it will get into the popular almanacks as well? Probably the future 200-inch reflector to be set up in California will tell more about it—& perhaps even help in locating still more distant planets. There is still quite a bit of interest in the limited solar system despite the diversion of astronomers’ chief notice to the larger problems of the stellar universe. Another thing that pleases me is that the newcomer came to light at the Lowell Observatory, & from Lowell’s own calculations. Poor chap! His better known observations & speculations never fared well in the scientific world; but now, thirteen years after his death, it is possible that his calculations may win him a major place among astronomers.(1)The road to Pluto is completed yesterday thanks to the New Horizons that finally shot the more detailed portrait of the dwarf planet: The most wonderful thing in all the mission is the precision of the calculations performed by NASA's scientists: I must remember to all reader that New Horizons tarveled for nine years in order to reach Pluto.

(1) H.P. Lovecraft’s Interest in Astronomy

(2) Lovecraft as Astronomer

(3) Tombaugh, C. W. (1946). The search for the ninth planet, Pluto. Leaflet of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific, 5, 73.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Markup Key:

- <b>bold</b> = bold

- <i>italic</i> = italic

- <a href="http://www.fieldofscience.com/">FoS</a> = FoS