Chaos is nothing more than order seen from the opposite side.This defintion by Fethry Duck in the italian story Il mobile caotico (The chaotic furniture) can be considered very centered on the heart of chaos. And the mathematical tool that we used to study it is the theory of chaos.

Flapping the wings

What best identifies chaos theory is the butterfly effect, which identifies in a simple and effective way the strong dependence of chaotic systems on initial conditions. The name was first used by Edward Lorentz, who published the first article on this effect in 1963(1).The popular version of the butterfly effect goes something like this: The flapping of a butterfly's wings in Brazil causes a hurricane in New York and the use of the butterfly was probably suggested to Lorentz from Ray Bradbury's 1952 short story A sound of thunder in which an unwary time traveler, stepping out of the path set by the travel agency and thus stepping on a butterfly, even manages to change the result of the last US presidential elections, allowing a fascist to become the most powerful man on the planet!

From a scientific point of view, one of the most typically chaotic problems is that of weather forecasts, because of the large amount of variables that are present. The appearance of chaotic behaviors, however, would not be so scientifically interesting if it were not for one of their particular characteristics: the fundamental laws that govern, for example, time are deterministic and individually easily solved, but by combining together a large number of such equations, not only the resolution of the system is more complicated, so much so that it is necessary to use electronic calculators, but also the solution shows a chaotic behavior graphically well identified by the Lorentz attractors:

Indeed the three-body problem is another typical example of a chaotic system, as emerged from the numerical resolution of the problem. Obviously the Sun-Earth-Moon does not show such ùchaotic patterns, but let's not forget that the solar system itself is much more complex than these three objects alone.

The central point of chaos theory is that, to obtain statistical behavior, it is not necessary to start from statistical laws, but it is the high number of variables that complicate the matter.

The statistical billiards

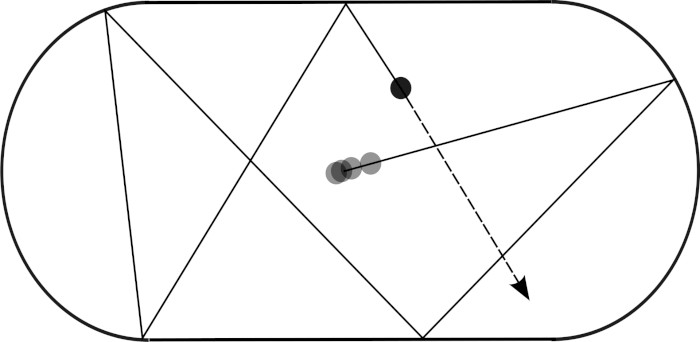

But what somehow simplifies weather predictions, making them somehow more accurate, is an interesting result known as Birkhoff's ergodic theorem, discovered in 1931 by the american mathematician George David Birkhoff. The theorem states that, although it cannot exactly predict the trajectory of a ball in a dynamic pool, it is possible to accurately predict how much time the ball will spend in a given region of the table. For example, if we are observing a gas, then even if we are not able to say exactly where its particles will be found at all times, we will still be able to predict quantities such as pressure and temperature.

Well, in 2011 the two mathematicians Corinna Ulcigrai and Krzysztof Fraczek studied a generalized version of the model, obtaining an unexpected result(4): the trajectories were not ergodic! Therefore, complicating the situation does not necessarily lead to chaotic behavior.

- Lorenz, E. N., 1963, Deterministic nonperiodic flow, Journal of the atmospheric sciences, vol.20, n.2, pp. 130-141 doi:10.1175/1520-0469(1963)020<0130:DNF>2.0.CO;2 ↩︎

- Leggi anche Chaos on the billiard table di Marianne Freiberger. ↩︎

- P. and T. Ehrenfest, Begriffliche Grundlagen der statistischen Auffassung in der Mechanik Encykl. d. Math. Wissensch. IV 2 II, Heft 6, 90 S (1912). ↩︎

- Frączek, K., & Ulcigrai, C. (2014). Non-ergodic $\mathbb {Z}$-periodic billiards and infinite translation surfaces. Inventiones mathematicae, 197(2), 241-298. doi:10.1007/s00222-013-0482-z ↩︎

No comments:

Post a Comment

Markup Key:

- <b>bold</b> = bold

- <i>italic</i> = italic

- <a href="http://www.fieldofscience.com/">FoS</a> = FoS