for their decisive contributions to the large project, which led to the discovery of the field particles W and Z, communicators of weak interactionThe story of this Nobel, however, began eight years earlier, in 1976. In that year, in fact, SPS, the Super Proton Synchrotron, begins to operate at CERN, originally designed to accelerate particles up to an energy of 300 GeV.

The same year David Cline, Carlo Rubbia and Peter McIntyre proposed transforming the SPS into a proton-antiproton collider, with proton and antiproton beams counter-rotating in the same beam pipe to collide head-on. This would yield centre-of-mass energies in the 500-700 GeV range(1).On the other hand antiprotons must be somehow collected. The corresponding beam was then

(...) stochastically cooled in the antiproton accumulator at 3.5 GeV, and this is where the expertise of Simon Van der Meer and coworkers played a decisive role(1).

The weak interaction

the weak interaction was introduced by Enrico Fermi in order to explain the results of the beta decay; Oskar Klein, however, was the first to suggest the existence of mediators particles valled electro-photons, thus suggesting that these mediators possess an electric charge(2).Subsequently, in a series of paper (the last was published in 1968), Sheldon Glashow, Steven Weinberg and Abdus Salam, pursuing an approach not so dissimilar to the formulation of quantum electrodynamics, built a model of the weak interaction, which provided not only the two charged bosons hypothesized by Klein, the $W$s, needed for beta decay, but also a new neutral boson, the $Z$(2).

The first step in the discovery of these three bosons was the detection of the neutral current at the bubble chamber of Gargamelle in 1973(3):

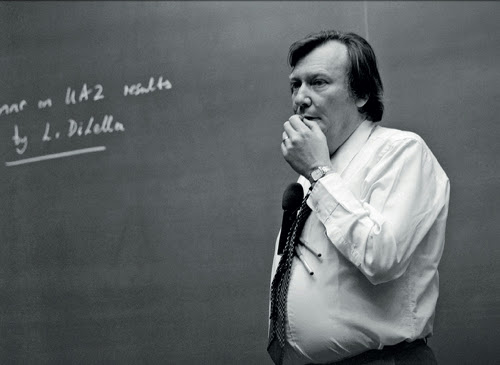

And this discovery was announced in January, 1983:

My family would have preferred that I took engineering

Carlo Rubbia was born on the 31st March 1934 in Gorizia and, as he remebers in an interview with Paola Catapano, his family would have wanted that he became an engineer:

(...) but I wanted to study physics. So we agreed that if I passed the entrance exams for the Scuola Normale in Pisa, I could study physics there, otherwise I would have to do engineering. There were only 10 places for Pisa, and I was ranked 11th, so I lost – and I started engineering at Milan. Luckily an unknown student among the first 10 in Pisa (whom I’d be curious to meet one day) gave up and left a place open to the next applicant on the waiting list. So, three months later, I was in Pisa, studying physics, and I stayed there and had a lot of fun.He graduated in 1957 with a thesis on cosmic rays. He then moved to Columbia University where he began a series of experiments on the nuclear capture and decay of muons, obtaining his PhD in 1959. Then he come back in Europe in 1960, for the CERN, which allowed him to obtain the prestigious Nobel Prize for the discovery of the weak bosons.

The next step of Rubbia, who held the post of director of CERN since January 1989 to December 1993, was the LHC:

The name LHC was invented by us – by myself and a small group of people around me. I remember Giorgio Brianti saying that the acronym LHC could not be used, because it already meant Lausanne Hockey Club, which was, at the time, much more popular for the lay public than a machine colliding high-energy protons. Nowadays things are quite different! We started with a programme that was much less ambitious than the US programme. The Americans were still somehow "cut to the quick" by our proton–antiproton programme, so they had started the SSC project – the Superconducting Super Collider – which would be a huge machine, a much more expensive one, but which was later abandoned. So, when my mandate as director-general finished, I left an LHC minus the SSC to the CERN community.

At Gran Sasso: the ICARUS project

ICARUS is a new generation of bubble chambers: this device is a tool that has been invaluable in the history of particle physics. Invented in 1952 by Donald Glaser, is a chamber filled with a liquid (preferably hydrogen) easily ionizable: in this way a charged particle that passes through the medium or that is created inside it, generates, yielding energy, a trace of bubbles ionized, and detecting them (still photography with a camera placed above the chamber) researchers can determine trajectory, energy, and particle type, also including the identification of the interaction, such as occurs, for example, for the neutral current in the photo of the 1973 just above.

Returning to ICARUS, there is to observe that the detector constructed to Gran Sasso is potentially able to detect the atmospheric neutrinos, also solar neutrinos, and also the much more ambitious first observation of the decay of a proton. It is also able to check neutrino oscillations.

The neutrinos exist in three distinct flavors, each associated with different neutrinos: electron neutrinos, the lightest; muon neutrinos, the middle ones; tau neutrinos, heavier ones.

These oscillations were provided by Ziro Maki, Masami Nakagawa and Shoichi Sakata in 1962(6) and subsequently revised in final form by Bruno Pontecorvo in 1967(7), obteining the famous matrix Pontecorvo-Maki-Nakagawa-Sakata: \[\begin{pmatrix} \nu_e \\ \nu_\mu \\ \nu_\tau \end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix} U_{e1} & U_{e2} & U_{e3}\\ U_{\mu1} & U_{\mu2} & U_{\mu3} \\ U_{\tau1} & U_{\tau2} & U_{\tau3} \end{pmatrix} \begin{pmatrix} \nu_1 \\ \nu_2 \\ \nu_3 \end{pmatrix}\] The first observation of such oscillation is in 1968, which was followed in 1969 by the famous article by Gribov and Pontecorvo, Neutrino astronomy and lepton charge, and the last point in this research is marked by the OPERA collaboration with the first observation of the oscillation from muon neutrinos to tau neutrinos. Experimentally, then, the idea is to measure the decays occurring inside the bubble chamber and from these determine what types of neutrinos that come out, using at the entrance of the chamber neutrinos of the same flavor.

The ICARUS T600 detector is so far the biggest LAr detector ever built. It has been successfully installed in the Gran Sasso underground laboratory and it is presently collecting data after having smoothly reached the optimal working conditions. LAr is a cheap liquid vastly produced by industry, which potentially permits to realize large mass detectors. ICARUS T600 represents the final milestone of a series of fundamental technological achievements in the last several years; its underground operation demonstrates that the ICARUS technology is now mature and scalable to much larger masses, in the range of tens of kton as required to realize the next generation experiments for neutrino physics and proton decay searches. Finally, the examples of neutrino interaction event analyzed in this paper demonstrate that also the reconstruction procedure is well under control fully exploiting the physical potentiality of this technology.(8)

Rubbiatron: energy amplifier

Rubbia was also interested in the neregy production. Indeed he often said that the future of the world energy will be in the renewables and nuclear ebergies, but not the ones we have available today. It is necessary to invest in research to make these two sources, respectively, more efficient and safer. In this field, in 1996, Rubbia proposed an energy amplifier, also known as Rubbiatron, a system for producing safer nuclear energy using thorium. These thorium reactors, which are currently developed mainly from China, have been suggested, even by the same Rubbia, as basis for a good interstellar propulsion system (pdf).

I do not know what the next page will be and I would prefer to let nature decide what we physicists will find next. But one thing is clear: with 96% of the universe still to be fathomed, we are faced with an absolutely extraordinary situation, and I wonder whether a young person who wants to study physics today, and is told that 96% of the mass and energy of the universe is yet to be understood, feels excited. Obviously they should feel as excited as I did when I was told about elementary particles. Innovative knowledge, the surprise effect, exists today, still continues to exist and is very strong, provided there are people capable of perceiving it.

Today the Nobel Prize in physics was awarded by Isamu Akasaki, Hiroshi Amano and Shuji Nakamura

for the invention of efficient blue light-emitting diodes which has enabled bright and energy-saving white light sourcesBut 30 years ago this prize was awarded to Carlo Rubbia, and recently we celebrated the CERN's 60th birtday. So I think that a post about Rubbia is the most useful thing in order to celebrate physics.

The weak bosons:

Papers by Glashow, Weinberg e Salam:

Glashow S.L. (1961). Partial-symmetries of weak interactions, Nuclear Physics, 22 (4) 579-588. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0029-5582(61)90469-2

Weinberg S. (1967). A Model of Leptons, Physical Review Letters, 19 (21) 1264-1266. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1103/physrevlett.19.1264

A. Salam, Proceedings of the 8th Nobel Symposium, Elementary Particle Theory, ed. N. Svartholm (Almqvist and Wiksell, Stockholm, 1968), p. 367

Experimental papers:

UA1: Arnison G., B. Aubert, C. Bacci, R. Bernabei, A. Bézaguet, R. Bock, M. Calvetti, P. Catz, S. Centro & F. Ceradini & (1981). Some observations on the first events seen at the CERN proton-antiproton collider, Physics Letters B, 107 (4) 320-324. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0370-2693(81)90839-x

Arnison G., B. Aubert, C. Bacci, G. Bauer, A. Bézaguet, R. Böck, T.J.V. Bowcock, M. Calvetti, T. Carroll & P. Catz & (1983). Experimental observation of isolated large transverse energy electrons with associated missing energy at, Physics Letters B, 122 (1) 103-116. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0370-2693(83)91177-2

Arnison G., B. Aubert, C. Bacci, G. Bauer, A. Bézaguet, R. Böck, T.J.V. Bowcock, M. Calvetti, P. Catz & P. Cennini & (1983). Experimental observation of lepton pairs of invariant mass around 95 GeV/c2 at the CERN SPS collider, Physics Letters B, 126 (5) 398-410. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0370-2693(83)90188-0

UA2: Banner M., Ph. Bloch, F. Bonaudi, K. Borer, M. Borghini, J.-C. Chollet, A.G. Clark, C. Conta, P. Darriulat & L. Di Lella & (1983). Observation of single isolated electrons of high transverse momentum in events with missing transverse energy at the CERN p collider, Physics Letters B, 122 (5-6) 476-485. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0370-2693(83)91605-2

Bagnaia P., R. Battiston, Ph. Bloch, F. Bonaudi, K. Borer, M. Borghini, J.-C. Chollet, A.G. Clark, C. Conta & P. Darriulat & (1983). Evidence for Z0→e e− at the CERN p collider, Physics Letters B, 129 (1-2) 130-140. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0370-2693(83)90744-x (pdf)

Papers by Glashow, Weinberg e Salam:

Glashow S.L. (1961). Partial-symmetries of weak interactions, Nuclear Physics, 22 (4) 579-588. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0029-5582(61)90469-2

Weinberg S. (1967). A Model of Leptons, Physical Review Letters, 19 (21) 1264-1266. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1103/physrevlett.19.1264

A. Salam, Proceedings of the 8th Nobel Symposium, Elementary Particle Theory, ed. N. Svartholm (Almqvist and Wiksell, Stockholm, 1968), p. 367

Experimental papers:

UA1: Arnison G., B. Aubert, C. Bacci, R. Bernabei, A. Bézaguet, R. Bock, M. Calvetti, P. Catz, S. Centro & F. Ceradini & (1981). Some observations on the first events seen at the CERN proton-antiproton collider, Physics Letters B, 107 (4) 320-324. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0370-2693(81)90839-x

Arnison G., B. Aubert, C. Bacci, G. Bauer, A. Bézaguet, R. Böck, T.J.V. Bowcock, M. Calvetti, T. Carroll & P. Catz & (1983). Experimental observation of isolated large transverse energy electrons with associated missing energy at, Physics Letters B, 122 (1) 103-116. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0370-2693(83)91177-2

Arnison G., B. Aubert, C. Bacci, G. Bauer, A. Bézaguet, R. Böck, T.J.V. Bowcock, M. Calvetti, P. Catz & P. Cennini & (1983). Experimental observation of lepton pairs of invariant mass around 95 GeV/c2 at the CERN SPS collider, Physics Letters B, 126 (5) 398-410. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0370-2693(83)90188-0

UA2: Banner M., Ph. Bloch, F. Bonaudi, K. Borer, M. Borghini, J.-C. Chollet, A.G. Clark, C. Conta, P. Darriulat & L. Di Lella & (1983). Observation of single isolated electrons of high transverse momentum in events with missing transverse energy at the CERN p collider, Physics Letters B, 122 (5-6) 476-485. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0370-2693(83)91605-2

Bagnaia P., R. Battiston, Ph. Bloch, F. Bonaudi, K. Borer, M. Borghini, J.-C. Chollet, A.G. Clark, C. Conta & P. Darriulat & (1983). Evidence for Z0→e e− at the CERN p collider, Physics Letters B, 129 (1-2) 130-140. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0370-2693(83)90744-x (pdf)

(1) Daniel Denegri (2003). When CERN saw the end of the alphabet. CERN Courier

(2) Rubbia C. (1985). Experimental observation of the intermediate vector bosons W , W-, and Z0, Reviews of Modern Physics, 57 (3) 699-722. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1103/revmodphys.57.699 (pdf)

(3) Cline D.B., Mann A.K. & Rubbia C. (1974). The Detection of Neutral Weak Currents, Scientific American, 231 (6) 108-119. DOI: 10.1038/scientificamerican1274-108

(4) Rubbia C., McIntyre P. & Cline D. (1977). Producing Massive Neutral Intermediate Vector Bosons with Existing Accelerators, Proceedings of the International Neutrino Conference Aachen 1976, 683-687. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-3-322-90614-4_67 (pdf)

(5) van der Meer S. (1981). Stochastic Cooling in the CERN Antiproton Accumulator, IEEE Transactions on Nuclear Science, 28 (3) 1994-1998. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/tns.1981.4331574 (pdf)

(6) Maki Z., Nakagawa M. & Sakata S. (1962). Remarks on the Unified Model of Elementary Particles, Progress of Theoretical Physics, 28 (5) 870-880. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1143/ptp.28.870

(7) Pontecorvo B. (1968). Neutrino Experiments and the Problem of Conservation of Leptonic Charge. Soviet Physics JETP, Vol. 26, p.984 (pdf)

(8) Rubbia, C., Antonello, M., Aprili, P., Baibussinov, B., Ceolin, M., Barzè, L., Benetti, P., Calligarich, E., Canci, N., Carbonara, F., Cavanna, F., Centro, S., Cesana, A., Cieslik, K., Cline, D., Cocco, A., Dabrowska, A., Dequal, D., Dermenev, A., Dolfini, R., Farnese, C., Fava, A., Ferrari, A., Fiorillo, G., Gibin, D., Berzolari, A., Gninenko, S., Golan, T., Guglielmi, A., Haranczyk, M., Holeczek, J., Karbowniczek, P., Kirsanov, M., Kisiel, J., Kochanek, I., Lagoda, J., Lantz, M., Mania, S., Mannocchi, G., Mauri, F., Menegolli, A., Meng, G., Montanari, C., Muraro, S., Otwinowski, S., Palamara, O., Palczewski, T., Periale, L., Piazzoli, A., Picchi, P., Pietropaolo, F., Plonski, P., Prata, M., Przewlocki, P., Rappoldi, A., Raselli, G., Rossella, M., Sala, P., Scantamburlo, E., Scaramelli, A., Segreto, E., Sergiampietri, F., Sobczyk, J., Stefan, D., Stepaniak, J., Sulej, R., Szarska, M., Terrani, M., Varanini, F., Ventura, S., Vignoli, C., Wachala, T., Wang, H., Yang, X., Zalewska, A., Zaremba, K., & Zmuda, J. (2011). Underground operation of the ICARUS T600 LAr-TPC: first results Journal of Instrumentation, 6 (07) DOI: 10.1088/1748-0221/6/07/P07011 (arXiv | CERN)

No comments:

Post a Comment

Markup Key:

- <b>bold</b> = bold

- <i>italic</i> = italic

- <a href="http://www.fieldofscience.com/">FoS</a> = FoS